Pisi Isip: The Questions Asked

by Ayesha Cala

How often do we fail to notice the voiceless in our lives?

Pisi Isip is a film centered around Gab, a mute boy turned artist, and Nico, his once-close friend, the film raises questions about how society treats the voiceless and marginalized.

The two start a wholesome friendship after Nico saves Gab from bullies, wherein Nico shortly after learns about Gab's passion for art and brings the mute boy home to show his own work. Their friendship progresses however, it abruptly ends after Nico faints one day and disappears.

A few years later, Gab is shown to be working as an artist for a corrupt politician. He is made to do the dirty work as he cannot speak about the things the mayor does behind the citizens backs. Gab’s employment under a corrupt politician starkly illustrates the moral cost of systemic corruption. His situation raises questions about agency and moral responsibility: Can someone without the means to resist truly be blamed for their complicity? What can the voiceless do when there is a mother, sick and dying, at home in need of medicine? Of money? And when Gab starts to question it – when he retaliates and speaks the truth in the only way he can, he is beaten. The medicine for his mother, wasted by the perpetrators of the violence done unto him.

Gab comes home just in time to catch his mother's last breaths as she advises him for one last time: ayaw pagpadaogdaog sa uban.

On the other side of the coin, an unnamed teacher is shown dealing with his cheating students, a stark parallel to how the people of authority can call out the wrongdoings of the people they govern and how those without power can rarely do the same to them.

The teacher starts walking a familiar path – the path to Gab's house. The teacher is identified to be Gab's once close friend, Nico.

Gab’s implied death by suicide is the film’s critical point. His revealed aspiration to become a sign language teacher, a vocation centered on giving a voice to others, underscores the loss of what he could have been.

The aftermath, particularly Nico’s grief and apology, shoulders the audience with the weight of unspoken words and unresolved guilt. While his disappearance was necessary as he went to the States to find the cure for his cancer, he never got to speak with Gab again. Nico’s realization came too late and he had already lost his friend. He was never at fault for leaving but it still leaves one to question: What is the responsibility we owe to those we care about?

Pisi Isip is a film with beautiful cinematography and fitting music. The contrasts of the vibrancy from the scenes of Gab's childhood and the muted colors of his time working for the mayor amplify the bleakness of the unwanted future he found himself in. Similarly, the choice of music was beautifully appropriate for the scenes they played in – lively in the childhood scenes, hair raising during the scenes of violence and melancholic on the apology.

Pisi Isip is not a film with a happy ending. At the end of it, Gab is tragically demised and Nico will still live with his regrets forever on his shoulders. The film gives the audience one final question:

How can we act before it’s too late?

Solace: The Gentle Refuge of the Soul

by Jelyn Genon

In the hustle and bustle of the city melodies, some people represent the forgotten note of this seemingly fast-moving sonata. Solace: quite a captivating word to describe a concept so profound that the trailer has not fully introduced it. Comfort. Consolation, especially at times of difficulties. Interestingly, the first impression one would discern from the films still would lean more on the ideas of brotherhood, or “bromance” to some extent—but I wouldn’t deny that it did give me an afterthought of some sort, perhaps, there is something about these two people walking in the street where “solace” would fit in. Regardless, every interpretation is subject to personal judgment.

The film unfolds the story of a young man who tries to navigate the harsh realities of life on the streets. He spends morning until night approaching strangers to beg for food and money. This prelude presents a raw, unabashed narrative centered on survival and resilience. The protagonist's life is marked by hardship and almost abandonment. It paints a striking representation of the street begging community as it highlights the varied reasons people end up in such dire circumstances. From washing dishes to gain a free meal to receiving support from fellow beggars, the film shows how these individuals often form bonds of camaraderie and solidarity even when they have so little. However, it also raises the question: why does a capable person, like the protagonist, resort to begging when they seem able to do more? This ambiguity is a weak point in the narrative, leaving the viewer to question the motivations behind his circumstances. Even when the familial issues he is currently facing are revealed, it does not seem to justify the “begging” considering that with how abled he seems, there are more pathways available for him to earn.

One of the more interesting moments comes when a compassionate stranger offers him food, groceries, and medicine—though I am not sure whether this gives more substance to the plot or simply is there to push through the idea of "consolation". The man’s gesture stands in stark contrast to the protagonist’s family dynamics, where his mother is sick and his father, an alcoholic, “sacrificed” himself for the family by working abroad for years only to go home to a pile of debt. These scenes offer a glimpse into the struggles of poverty, familial sacrifice, and the complex nature of love and responsibility. From how I see it, this may be a way to give the audience an idea of the motivation that drives our protagonist to beg, however, the execution fell short when it did not seem to convince me, the audience, that it is justifiable.

This young man, whose life has been a series of downs and falling again even after trying to fly, finds solace in the memory of his late uncle—an influential figure who had dreamed of teaching him how to play the guitar. In a poignant twist, his uncle's death, which occurred before that dream could be realized, becomes the catalyst for a deeper reflection on faith, loss, and the pursuit of passion. His visits to the cemetery laid the central theme of the film… a nostalgic reminiscence of the bittersweet hymn of yearning. His uncle's faith in music left an indelible mark on our protagonist who strayed far away from the burning fervor of strumming the guitar, to singing, to becoming music in itself.

The ambiguity surrounding the protagonist’s uncle’s background and his impact on the young man's love of music is one of the movie’s main flaws. The movie makes the suggestion that music can help people be resilient, but it doesn't go deep enough into that relationship to make the emotional payoff powerful. The movie's conclusion also seems hurried. Although it is clear that music has inspired hope, it is unclear how the protagonist's life will change as a result of this newfound motivation. The audience is left to wonder if music truly becomes a means of transformation, or if it is just another fleeting solace in a world full of unanswered questions.

The film’s central theme—music as solace—is effectively portrayed, though the exploration feels underdeveloped. While the protagonist’s bond with music is clear, particularly through his uncle’s legacy, the film doesn’t delve deeply into how this passion of his was realized, and how this rekindled passion will shape his future. It hints at the potential for music to be a path to healing and self-discovery, but the resolution remains vague. Another possibility is that the consolation and comfort that music can provide is not “automatic,” meaning, we might need that one, light tap in the shoulder, or perhaps, a gentle embrace that reminds us we are not alone. Maybe, we just really need to be encouraged or to be reminded of the beautiful life that our loved ones have lived while they are still in this world. This consolation amid grief and regrets offers a profound re-exploration of our capacity to make meaning even in suffering. It is conceivable that the strength of this film— is hope.

‘Gulong ng Tadhana’: A Good Man’s Sacrifices

by Fatmah Said

We all merely toil under the wheel of fate. It is a familiar and intimate struggle: to watch our loved ones wake up at the crack of dawn, barely being able to say goodbye before they stumble out the door, ready to take on their two or three successive jobs. Afterward, they return late at night, exhausted and spent. Then, they repeat it all over again in a merciless cycle. All of this, just to stave off the threat of financially going under. Gulong ng Tadhana, directed by Erl John Luise Baculio, is about difficult choices. What is ‘right’ is rarely easy— sometimes, it is even painful. Atom Gomez, a driver for hire and father, must walk a tightrope trying to balance his obligations: to his wife, to his boss, and to his moral character. While the film presents a compelling struggle between a man’s duty and his desires versus his principles, it struggles in its portrayal. Between awkward and unfulfilling characterization and unrealized thematic beats, perhaps the notion of “the concept is better than the execution” rings— unfortunately— true.

The film follows the previously mentioned Atom Gomez, who works as a driver alongside other miscellaneous jobs to provide for his heavily pregnant wife, Delia Gomez, and his children. Atom; what a fascinating name for his character. The name invokes an infinitesimal size– perhaps alluding to Atom’s position as a lower-rung worker, as evidenced by his need to juggle between low-paying jobs and being especially known for doing so by the people in his life: his wife, his drinking buddy, and especially his boss, who calls him just after his work hours and offers him money in exchange for the tedious task of receiving and delivering his files from the office. Atom Gomez evokes the stereotypical profile of many Filipino men: the family man, the family provider, the busybody, and the (recovering) alcoholic. As the film’s protagonist, he is especially subject to its theme; literally revolving around him and his choices. The struggle between his obligations, his desires, and his morals— and, of course, the consequences of neglecting one over the other. Each supporting character represents an angle of this struggle, although I would argue that not all are able to provide a satisfying, consistent representation of these facets in Atom’s arc.

Delia represents Atom’s obligation to his family. She is his wife and is heavily pregnant with their third child. An interesting aspect of Delia’s character is that she occupies a paradoxical position in Atom’s life: being both the most important and least important person to him. Yes, Delia is the reason why Atom works so hard and tries to tone down his drinking habits, yet she is the one who Atom neglects and ignores most in the film. When they talk in the morning before Atom goes off to work, Delia is consistently the only one leading the conversation, while he is mostly quiet. He only bothers to speak when spoken to. When Delia asks him to come back home earlier, he agrees— only to immediately forsake his word at the promise of payment in exchange for his time. Time that could have been spent with his actual family. Time that could have saved Delia. There is no bigger representation of the theme of sacrifice than Atom’s choices regarding his wife. When he ignores her call and desperate plea for him to come home in favor of helping another character, the consequence of his neglect comes in the form of Delia’s sudden death during labor. Here, the film presents a clear outcome of Atom’s severe neglect of the person who represented his entire family and his entire motivation for working. An unintended sacrifice that could only result in a loss.

While Delia represents Atom’s obligations in the film’s binary struggle between duty and morality, Aly represents the other half of the coin– although she may be an unconventional representation of such. Little can be inferred from Aly’s character during her introduction, only that she is talkative, a party girl, and clueless, often to her detriment. She contrasts well with Delia, who is painfully aware of her role as a wife and mother. Aly’s role in the film is the Chekov’s gun: while she seems to only be another passenger during Atom’s shift, she re-appears to provide Atom with his dilemma: to choose between his obligation or his principles. While Atom is driving back home in response to his wife’s call, he becomes the only witness to an assault. The victim, it turns out, was Aly; the same girl he drove to a party earlier. Due to her drunken state, she was unable to notice two men stalking her until they had already pinned her down. Atom, who was well aware of his wife’s condition, made his choice, stopped the car, and fought off the attackers. Afterward, he drives her back to the police station to drop her off, instead of leaving her to wander home alone once more. Although he could have chosen to leave her and drive home, he, instead, chose to ensure the girl’s safety. In sacrificing Delia, Atom saves Aly. Another cause-and-effect in line with the theme that was done effectively.

Except— there was still the inclusion of the police station scene. During this, the film attempts to insert another line of cause-and-effect, wherein if Atom does not stay for the police interview, he will immediately become the top suspect in Aly’s assault case. This is due to how recent victims are often in an altered state of mind, and thus unable to provide a reliable testimony. If Atom were to stay, he would further the time spent away from his wife, but it would ensure he would not be wrongly suspected of assault. If he were to leave, he may have to deal with a future criminal case or record and all the problems that would entail. Here, Atom again makes a choice: now, he chooses his wife. He leaves the police station without further notice and risks potential trouble with officers later on. Now, as established in the previous two cases, these dual choices carry consequences with them— with the neglected party ‘punishing’ Atom, while the chosen party entails fulfillment. Strangely, despite the consequences being so heavy-handed (with the policeman telling Atom what would happen if he were to neglect protocol), the film never again addresses or even alludes to the stated suspect charges at all. Atom suffers no consequences for neglecting his civic duties. Neither positive nor negative. Just— nothing. It is an unsatisfying plot thread that goes completely unaddressed in the rest of the film despite the already-established consequences.

The last character suffers the worst form of unrealized thematic cohesion: Atom’s boss— also referred to as simply the manager. He was made to represent Atom’s work obligations. His dedication to his livelihood as a means to provide for his family. The manager appears early on in the film, requesting Atom to fetch his files from the office in exchange for extra pay. He is portrayed to be professional, but perhaps exploitative of his worker’s desperation for money. This plot thread happened simultaneously with the previous cases and was definitely meant to contribute to the push-and-pull between Atom’s obligation and morals. In fact, the manager was the initial reason Atom had stayed out late before encountering Aly again. Atom’s dedication to earning money cost him his time with his family and his initial promise to his wife. However, as the film progresses and reaches the far more intense scenes, Atom’s dedication to his boss is put on the back burner. In fact, it would be easy to forget that Atom agreed to the job in the first place. Of course, when the manager calls Atom, frustrated, to inquire about his whereabouts and his files, it becomes evident that Atom has forgotten and neglected another one of his duties. From the other interwoven struggles and consequences, it would make sense for Atom to receive another ‘punishment’ in fulfillment of the thematic beats and what we can expect from the character. Only, we do not get that. When Atom explains his situation with his wife and her current condition, his boss, despite showing clear irritation at the neglected demand, immediately forgives and understands him, offering nothing else than well wishes. Perhaps his reaction was meant to be an inversion of what the audience would expect from the character, and perhaps I would be inclined to agree— if it was not for the fact that it makes the weight of his character and representation completely moot. In the first place, all the representative characters provided some form of clear consequence if they were to be neglected (Delia going into painful labor in the house; Aly being assaulted; the police station determining Atom to be the top suspect), and the manager’s status as Atom’s superior allows him to contribute another form of tension and fear: from the mundane painful disappointment and lost trust in Atom, to the potential loss of the driver’s job. Yet, Atom receives none of this, which strays so far from the film’s thematic line of questioning and exploration of consequences. The manager is, literally, inconsequential. Thus, it also makes his character practically pointless. If the film wishes to tighten its thematic cohesion while freeing up time, then the character of the manager should have been removed. Then, the rest of the film would have been spent exploring the promised outcomes of Atom leaving the police station with no second thoughts. Honestly, it could have also just focused on Atom’s struggle with Delia and Aly, without the added scene at the police station for a more efficient use of the film duration.

The interwoven nature of our fates and our obligations to one another. The question, ‘What are the consequences of my choices?’ frequently defines many of its story beats and determines many of the characters’ fates. Some are more forgiving than others. The film’s portrayal of regular people just trying to get by and inadvertently affecting each others’ lives is a fascinating take on the nature of fate, wherein it is merely the outcome of the actions of other people, may that be good or bad. Perhaps, our actions cannot be simply defined or described with the binary of good and bad, as after all, what may feel ‘good’ or look ‘right’ is ultimately the most damning choice. After all, what is right is never easy, and what is ‘good’ may simply be selfish. Nevertheless, the film also posits the importance of living with our choices and fates. After the faults are realized and when hindsight hits, we cannot turn back the clock and re-do our decisions. We can only march forward, turning along with the wheel of fate.

Bilangkad: The Greatest Good or The Greatest Guilt?

by Samuel Harry Adlaon

Have you ever done something you believed was the right thing, only to realize later that it became your deepest regret? “Bilangkad” offers us a truthful narrative about the reality of sex work using the ethical philosophy of utilitarianism. The film starts with what could be considered a typical Filipino household morning—the blabbering of a mom. Right away, we see the relationship dynamics between the protagonist, Alma, and her family—her mom and her sister, Emma. Alma’s mom, highly stressed about her sick daughter, pressures Alma to find a job to support the family. A quick representation of what many eldest Filipino daughters experience, I might say. This moment sets the plot for the entire film.

From the start, Alma experiences slut-shaming. With her bold red lipstick—often used in films to represent audacious women—she gets called a slut by her mom. And for what? Just for trying to make herself look presentable for job opportunities. Throughout the film, Alma’s mom doesn’t fail to remind her of how “promiscuous” she supposedly is, throwing words like “sig bilangkad” and “burikat” at her. All this ignores the main reason Alma is putting herself out there: to find a job that can help support her family. This makes us question: what does this say about us and our views on sex workers?

Before diving into that, let’s discuss the ethical theory at play here. Utilitarianism is a moral philosophy that evaluates actions based on their consequences, specifically focusing on maximizing overall happiness or well-being. For me, the film presents two major ethical dilemmas that Alma faces.

The first is Alma’s decision to enter sex work as a way to earn money. It’s important to note that Alma was already being slut-shamed even before she stepped into the sex industry. She knew the consequences and the guilt that would weigh on her if she entered that world, but she did it anyway—for her sister. Utilitarianism tells us to choose the action that brings the most benefit, and in this case, Alma chose sex work because it would provide for her family, outweighing the personal costs she would endure.

This highlights a stark reality of sex work—contrary to the sanitized portrayals of choice feminism, where sex work is framed as empowering, Alma’s decision is rooted in survival rather than agency. Like Alma, many sex workers enter the industry out of necessity, as shown through her friend Gina, who also turns to sex work to make ends meet. Choice feminism has tried to reframe sex work as this girl-boss, slay-mother career that any woman can just jump into, but this narrative erases the real struggles and reasons people enter the industry. Sure, we can all agree that sex work is work, but it’s not an easy job anyone can casually take on. Most sex workers are there not because they want to be, but because they have to survive. Alma and her friend Gina are perfect examples of this—they’re in the industry because they need the money.

The film does a fantastic job of showing the mental anguish Alma goes through after her first client. She feels empty and used, she had a yelling outburst after her mom slut-shames her, not knowing the reason so, hence, “wala lang man ka nangutana na unsa ko?” but she pushes those feelings aside after they hear Emma cough, she pushes it aside because she has a job to do: make enough money to pay for her sister’s medical bills.

The second ethical dilemma comes when Alma must choose between Gina’s life and her sister’s life. Alma is offered money if she kills Gina—money she desperately needs for her sister’s medication. She faces two unbearable choices: to kill her friend and get the money, or to refuse and lose the chance to help her sister. In utilitarianism, the morality of the action isn’t about the action itself but the consequences. Alma chooses to kill Gina because saving her sister’s life is the “greatest good.”

But the film doesn’t stop there. It pushes us to confront the imperfections of utilitarianism. After Alma kills Gina, she rushes to her sister’s room, ecstatic to announce she got the money—only to find her sister lifeless. In that moment, all of her sacrifices—the shame, the pain, the blood on her hands—are for nothing. Her sister is gone, and Alma is left with guilt and grief.

This perfectly illustrates the flaws of utilitarianism: a theory that focuses on achieving the greatest good but doesn’t account for the absurdity and unpredictability of life. What happens when the “greatest good” becomes your greatest guilt? Alma is left to live with this burden, perhaps comforting herself with the thought that she did what she believed was best at the time.

As an audience, we are forced to face these moral complexities. Despite all the actions and decisions Alma made, life remained cruel and unfair. “Bilangkad” reminds us that moral decision-making is rarely black and white. It’s messy, filled with absurdity, and often leaves us questioning if we did the right thing.

Bente Seis: A Story of Loss, Redemption, and the Power of Empathy

by Michaela Pastoriza

What do we do when the person we hate the most is staring back at us through the eyes of someone we love?

This is the provocative question at the heart of Bente Seis, a film that masterfully weaves together the complexities of grief, prejudice, and redemption. It appears to be a story about addiction, but beneath the layers lies a deeper exploration of morality, human judgment's fragility, and empathy's redemptive power.

Winston, the film’s central figure, begins his journey with a noble yet naive belief: that he can help everyone. His passion for social work stems from this idealism, but an unshakable disdain for drug addicts also mars it—people he views as weak and reckless, those who, in his mind, choose their suffering. His contempt is not random; it is born of personal tragedy. Winston lost his parents to drugs, and in the wake of that trauma, he built a wall of judgment to protect himself from the pain of understanding. Life, however, has a cruel way of dismantling the walls we build around our hearts. Winston’s best friend, the one person he believes has everything figured out—a stable home, supportive parents, and endless potential—suddenly falls victim to the very thing Winston despises. What starts as late nights at a fraternity turns into full-blown addiction. And then, one night, without warning, Winston’s best friend is gone—dead from a seizure caused by a drug overdose.

The grief is suffocating. But it’s not just grief. It’s rage. It’s guilt. It’s confusion. How could someone so full of life, someone who seemingly had no reason to choose this path, end up here? Winston is forced to confront an unbearable truth: maybe it wasn’t a choice. It is here, in the wreckage of his grief, that Winston begins to see the truth: addiction is not a simple choice. His best friend didn’t choose this path out of weakness or malice. Addiction, the film suggests, is a symptom of deeper wounds—unspoken pain, societal neglect, or unhealed trauma. Winston’s long-held hatred begins to crumble under the weight of this revelation.

The death of his friend becomes a painful yet powerful turning point. Winston realizes that the people he once condemned are not so different from himself. He sees their humanity, their struggles, and their yearning for hope. In his friend’s memory, Winston dedicates himself to a new mission: helping those he once despised. As a counselor, he becomes a light for those fighting addiction, breaking the very cycle of judgment that once defined him.

At its core, Bente Seis is not a story about drugs—it’s a story about the transformative power of empathy. It challenges us to confront our own biases and reminds us that morality is not a rigid framework of right and wrong but a fluid, evolving understanding rooted in compassion. Winston’s journey is a testament to the idea that even our deepest wounds can become the foundation for our greatest growth.

This film left me with lingering and uncomfortable questions: How many people have we judged without ever understanding their pain? How many people have we lost—not because they were beyond saving, but because we refused to see them?

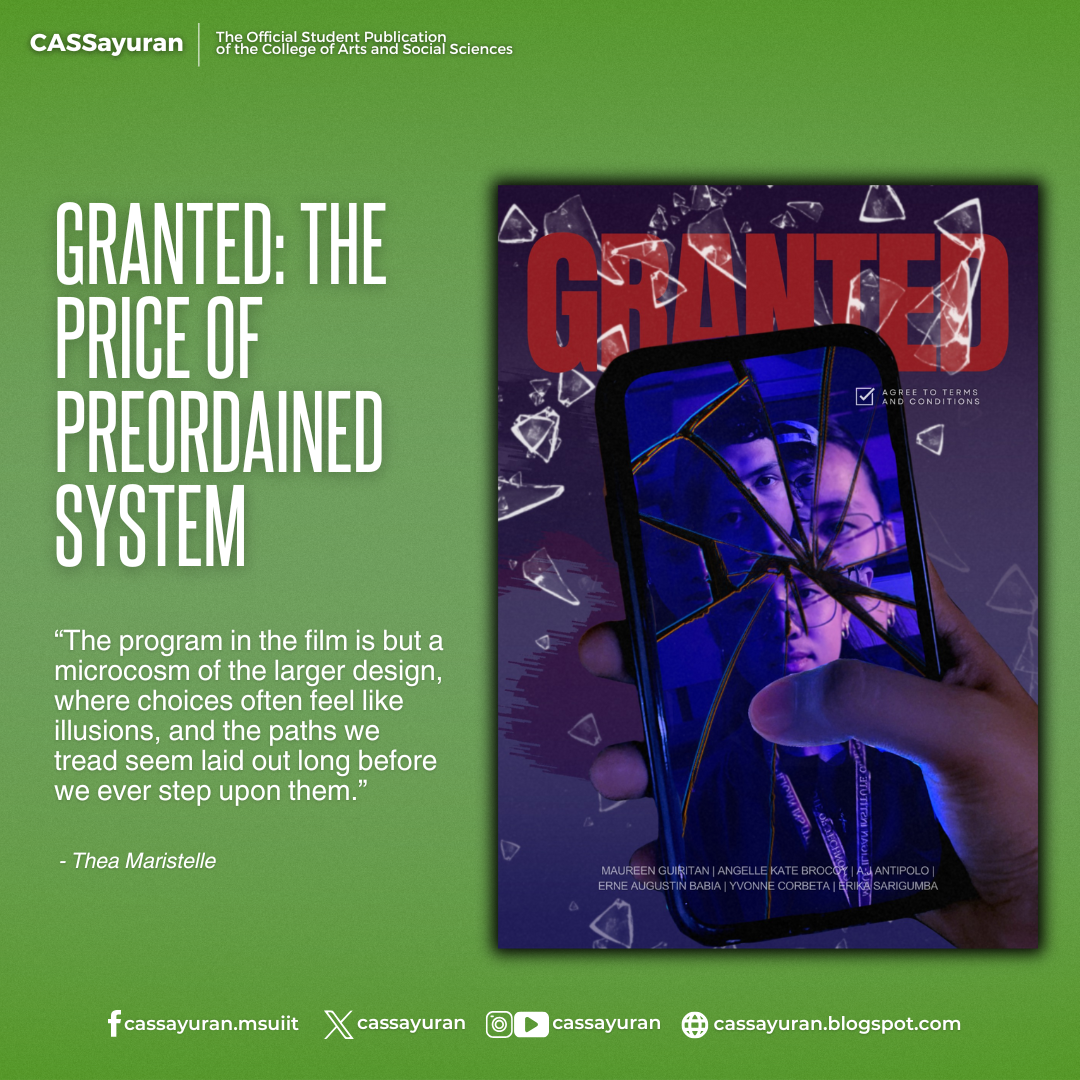

Granted: The Price of Preordained System

by Thea Maristelle Pusod

Life often feels like a series of choices presented in stark contrasts—dreams versus survival, ambition versus morality. The film opens with Velia, a college student trying to carve out a future in the quiet hum of her family's sari-sari store. Her life is one of quiet desperation, each day a reminder of the difficult choices ahead. Then it came—an unexpected package, its black exterior a sharp contrast to the mundane world she knew. Inside, an invitation to a scholarship program. The promise of a future beyond her current reach, a future bright with possibilities. It was a lifeline, or so it seemed. Velia, with little more than the determination she had carried all her life, took the plunge. She would enter this world of opportunity, this world that whispered of something greater, something better. It was her chance. Yet, as she steps closer to this glimmer of hope, the journey ahead slowly morphs into something darker, leading her into a labyrinth where each choice twists deeper into a tangle of moral compromises

At first, the scholarship program appears to offer salvation, structured around exams and tasks designed to test aptitude and endurance. But the veneer of opportunity quickly dissolves, revealing an unrelenting series of physical, mental, and ethical trials. Velia and her peers, including Ruby—her friend whose body succumbs to the toll of performance-enhancing drugs given to help them survive—are hauled into a system that thrives on their desperation. Rumors swirled among the participants, stories of others who had vanished. A brilliant student, once part of the program, had simply disappeared—no goodbye, no explanation. Her absence lingered in the air, a heavy silence that spoke louder than any words. What happened to those who failed? What price would they pay for the privilege of ambition? This absence serves as both a warning and a grim reminder of the stakes: failure doesn’t just mean losing the scholarship—it may mean losing everything.

Granted is not merely the story of a scholarship program; it is a scrutiny of the systems that govern our lives—systems that promise fairness but often reveal an unspoken inequality. The scholarship, meant to uplift, becomes a crucible where ambition is tested against humanity. Here lies the film's brilliance: its ability to narrate contractarian and utilitarian principles into a visceral experience. The program’s implicit demand for sacrifice and its manipulation of vulnerability reveal the cost of a society that prizes achievement at any cost.The program’s trials—grueling to the point of breaking—echo the sacrifices many make in the pursuit of success. Yet, the film also asks: at what point does ambition become self-destructive? Can one retain their humanity while striving for a better life in a system designed to dehumanize?

The film’s cliffhanger ending—Velia receiving a text confirming her acceptance into the program—leaves these questions unanswered. Has Velia triumphed, or has she simply become another cog in the program’s unrelenting machinery? The absence of resolution is intentional, echoing the uncertainties of real-life choices where the moral cost of success often remains unclear.

In the end, it is a quiet, unsettling echo of the systems that shape us, like strands of DNA preordaining the contours of our choice. These systems mold us, not as architects of our own destinies, but as prisoners, bound by invisible chains of ambition. The program in the film is but a microcosm of the larger design, where choices often feel like illusions, and the paths we tread seem laid out long before we ever step upon them.

And so, we are left to confront the price of ambition. Is it a noble pursuit, a lifeline to escape the constraints of circumstance? Or does it become a slow unraveling of the self, stripping away pieces of our integrity until all that remains is the hollow shell of a dream? How much of ourselves are we willing to surrender to systems that promise success but demand our humanity in return? It is a question we must all confront, in a world where the cost of ambition often feels like a debt we are doomed to carry.

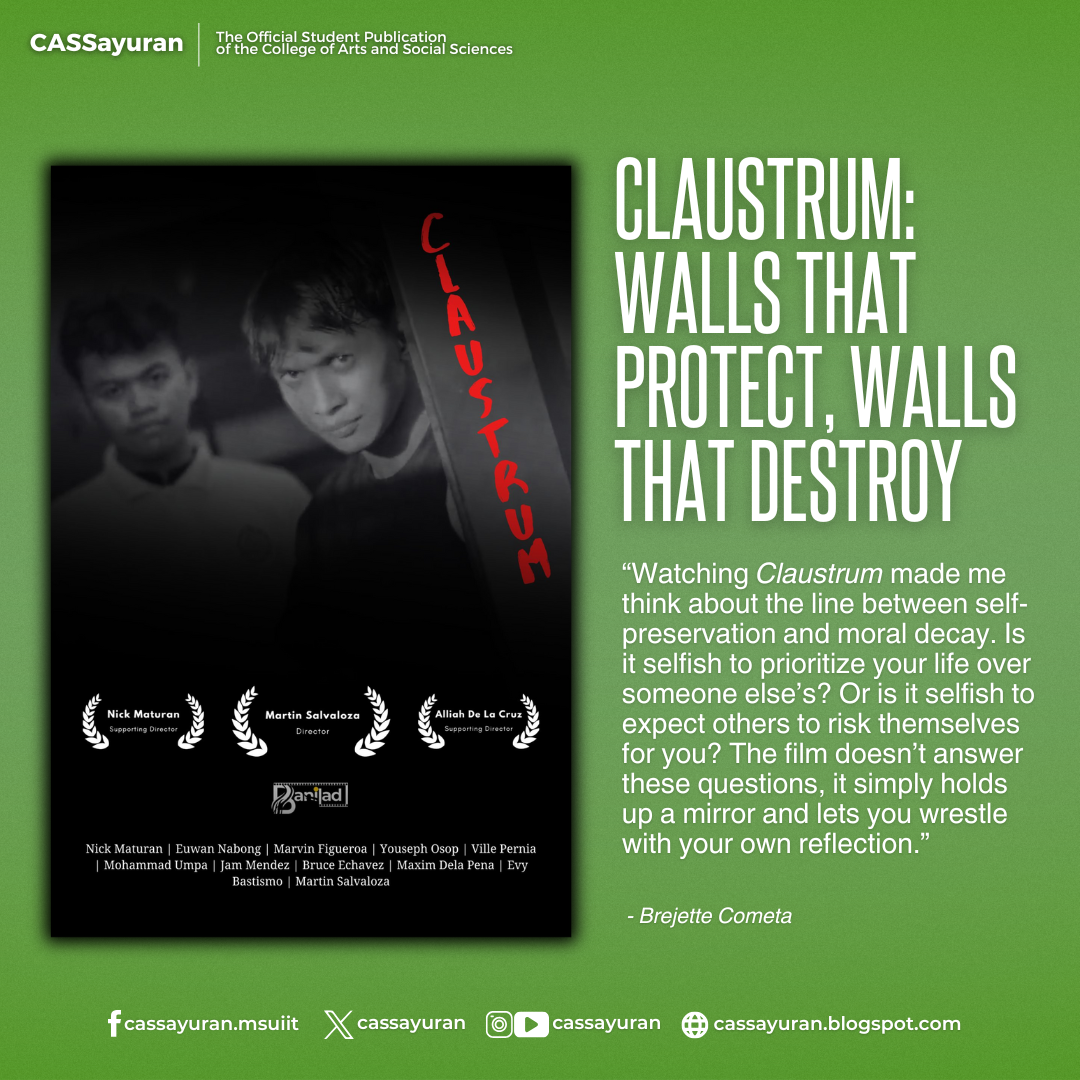

Claustrum: Walls That Protect, Walls That Destroy

by Brejette Cometa

They never saw it—not really. It was there, looming, a presence that gnawed at their minds, but the "it" was never shown, never explained. In some ways, that made it even more terrifying, making the struggle more visceral, more internal. Claustrum doesn’t explicitly tell you what “it” is, the threat that forces the characters into isolation. Maybe it’s a monster, or maybe it’s just the world collapsing in on itself.

The film unfolds six months after a group of friends has barricaded themselves in a house surrounded by a tall gate. The outside is death. They know this because the ones who ventured out never came back. Inside, they tell themselves they’re alive, but what does survival mean when everything human starts eroding?

Section I: A Brother’s Love

In the opening act, we see the relationship between two brothers—or at least, brothers in spirit. This isn’t a tale of familial bonds, but of duty in its purest form. When one brother is injured, the other decides to venture outside to look for essentials. This decision isn’t made out of a sense of obligation, but rather a mixture of love, fear, and the human need to take action in the face of uncertainty.

What makes this choice significant isn’t its nobility, but the intensity of it. The brother’s departure is not romanticized or glorified. There’s no over-the-top heroism here. Instead, we witness a decision born from the basic instinct to protect and care for another. The decision to go outside represents something fundamental, a moment of uncertainty in which survival is not guaranteed, and yet, it feels like the only thing to do. The act is not a painful burden, but it's an emotional response to the situation—an attempt to right what feels wrong, even when the path ahead is unclear.

Section II: Guilt

Another member of the group, restless and unable to accept the loss, asked the injured man about the one who had left. Was there a chance he could still be alive? Could he have survived? That guilt and hope drove him outside the gate, following in the footsteps of the lost. He, too, never returned. But the film doesn’t indulge in false hope. It shows how this futile quest leads only to further loss. Watching that unfold, I couldn’t shake the question—how far would we go to chase the shadow of a lost person, even knowing deep down that they’re gone? Was it love, guilt, or the stubborn refusal to face the finality of death?

Section III: Angst

The tension explodes as the group begins to fracture. They fight with fists and with words that cut deeper. They argue about survival, purpose, and who truly belongs. It’s brutal because, as a viewer, you see their frustration, the creeping nihilism of a world where staying alive has no meaning unless there’s something to live for. But purpose is a slippery thing. For some, it’s just about getting to tomorrow. For others, it’s about protecting what’s left of their humanity. And for a few, it’s about control—the ability to decide who gets to stay and who has to go.

The Meeting

During the group's meeting, the debate over dwindling resources grows into something far more sinister. It’s a perfect example of human nature under duress. Fear and desperation corrode compassion. The injured person is no longer a friend or a comrade, he's now a "problem" to be solved. This cruelty mirrors how, in real life, crises often force people to make choices they later rationalize but may never truly forgive themselves for.

It’s easy to judge the characters for their choices, to call them heartless. But what would any of us do if we were in their position? When resources are finite and death is knocking at the door? The tragedy of this moment isn’t just that they abandon the injured member—it’s that they’ve turned him into a utilitarian equation. The exchange is about survival at any cost. This cruel pragmatism serves as a mirror to real-life crises, where the value of human life is often measured in terms of utility, and decisions are rationalized through a lens of cold logic. This dehumanization is uncomfortable, but it’s an uncomfortable truth that the film lays bare. It shows that when resources are finite, compassion is often the first casualty.

Section IV: Betrayal

The rebellion of the character who dares to defy the group’s decision is heartbreaking. He searches for the injured man, seeking to undo the betrayal, but this defiance only leads to further fracture. The group, already splintered by fear and desperation, is now torn by personal moral dilemmas. This rebellion isn’t just about one man going rogue, it’s about the decay of trust and unity, the collapse of what little holds the group together.

What is betrayal in this context? Is it merely the breaking of trust, or is it something more? The injured man is abandoned, not out of malice, but because survival demands such sacrifices. The film doesn’t condone this choice, it doesn’t need to. Instead, it simply forces us to look at the gray areas of human morality. Betrayal, here, is both a survival mechanism and a moral breakdown. It’s a reminder that sometimes, survival is a poison that eats away at everything we value.

Section V: Selfishness

Then there's the girl outside the gate, asking for help. The girl’s cries linger as one of the film’s most haunting moments—not because of her desperation, but because of the group’s silence. Their refusal to act is born out of fear. They’ve already sacrificed so much to stay alive, and responding to the girl would risk everything they’ve fought for. This serves as a microcosm of the film’s overarching theme: the walls we build to protect ourselves may save our lives, but they destroy the parts of us that make life worth living.

Here, we see that selfishness isn’t always loud or violent. Sometimes, it’s just the act of turning away, of pretending you don’t see the suffering because acknowledging it would demand too much of you.

Claustrum’s brilliance lies in its subtlety. The threat outside the gate is never shown because it doesn’t need to be. The real terror is inside, whispering doubts, feeding fears, and slowly stripping away everything.

In the end, the film asks whether survival is even worth it when all that’s left is a shell of what you used to be. Maybe the real claustrum is the walls we build within ourselves, the ones that keep us alive but leave us empty. But the film complicates this idea. Selfishness might keep you alive, but at what cost? The group’s decisions ensure their survival, but they also strip away their humanity piece by piece.

Watching Claustrum made me think about the line between self-preservation and moral decay. Is it selfish to prioritize your life over someone else’s? Or is it selfish to expect others to risk themselves for you? The film doesn’t answer these questions, it simply holds up a mirror and lets you wrestle with your own reflection.

My Kuya, My Hero: On Family, Sacrifice, and Love

by Samuel Harry Adlaon

It was so easy for him to sacrifice anything—his health, his education, even his pain. For Kuya Juno, sacrifices were a testament to his immeasurable and sacred love for his sister.. “My Kuya, My Hero” captures the unbreakable bond between a kuya and his sister, highlighting the everyday sacrifices our loved ones make, that are often unnoticed. The film introduces us to Juno, the main protagonist, alongside his sister Abby and his loyal friend Uncle Kade. The film’s central theme is Ethics of Care, a moral theory emphasizing the importance of relationships and the responsibility to care for those who are dependent and vulnerable. Juno’s actions resonate deeply with this framework, showcasing the depth of his commitment to his sister’s well-being. The Ethics of Care emphasizes the moral significance of caregiving in human life, and Juno exemplifies this through his relentless efforts to provide for Abby despite his struggles.

For me, a recurring and powerful symbol of sacrifice in the film is the sikad, which was prominently featured in the movie poster and serves as a constant reminder of Juno’s dedication. When Juno loses his construction job, he refuses to give up and turns to driving a sikad to sustain Abby’s needs. The pedicab becomes more than just a means of livelihood; it symbolizes Juno’s resilience and his unwavering determination to provide for his sister. The sikad became a constant signifier of the sacrifice he had to make, from bringing her sister to school to making it a source to make ends meet.

Juno and Kade both endure immense hardships to survive. As working students, they juggle academics and work, a feat requiring perseverance and selflessness. Similarly, Kade’s sacrifices mirror Juno’s as he works tirelessly to support himself and his friend, even selling balut to make ends meet.

The film’s narrative peaks during the climax - Abby’s birthday, an emotional moment where Juno’s unwavering love takes center stage. Despite the challenges, Juno and Kade go out of their way to make the day special for Abby, a testament to their heroism - they even had a heart to heart talk one night about how they’ll spend her birthday, a conversation reminding us that even on our joyous days sacrifices had to be made. However, the film also highlights Abby’s sacrifices. She gives up her innocence, revealing her vulnerabilities ultimately strengthening her bond with Juno. Her willingness to acknowledge her kuya’s struggles and express her gratitude deepens their relationship, showcasing the reciprocal nature of their sibling love.

In her heartfelt poem titled “My Kuya, My Hero,” Abby describes Juno as her provider, protector, and silent sufferer—a kuya who lies about his strength but cries in secret, bearing his burdens alone. Her words, “Salamat, Kuya” (Thank you, Kuya), encapsulate the gratitude and admiration her sister had for his sacrifices.

The film’s strength lies in its ability to depict the nuanced dynamics of familial love and the unspoken heroism of caregivers. Juno and Kade are not merely supporting characters in Abby’s life but are also her shelters, her heroes, and her unwavering pillars of support. Through their struggles, the film reminds us of the quiet yet profound acts of love and sacrifice that shape our lives. From small scale sacrifices to major ones.

Ultimately, “My Kuya, My Hero” is a perfect exploration of Ethics of Care, celebrating the heroes among us who prioritize the well-being of others above their own. It invites viewers to reflect on the sacrifices of their own loved ones and to cherish the relationships that form the foundation of their lives. Someone in your life might be the Kuya Juno or Uncle Kade, remind them that their sacrifices do not go unnoticed. Show them compassion and gratitude, that they too are also cared for.

Post a Comment

Any comments and feedbacks? Share us your thoughts!